Research

The Kirby Laboratory conducts translational research at the interface of antimicrobial discovery, clinical microbiology, and bacterial pathogenesis. Our work integrates high-throughput screening, pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic modeling, and clinical microbiology diagnostics to address unmet needs in infectious diseases.

Detailed and up-to-date information on ongoing projects, publications, and opportunities is available at https://www.kirbylab.org

Antimicrobial Projects

Therefore, the Kirby Laboratory, funded by grants form the National Institutes of Health, is taking a number of approaches to identify and develop next generation antimicrobials. Our approaches build on an understanding of how bacterial pathogens causes disease and evade therapy by current antibiotics.

(1) Attacking the biology of gram-negative infection.

(2) Screening for inhibitors that act on the pathogen, pathogen-host interface, and/or host cells to limit intracellular bacterial replication.

|

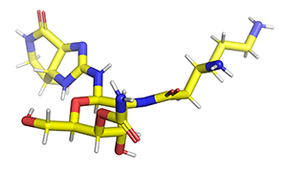

We recently described a novel high throughput screening technology(highlighted on the cover of the May issue of Assay Development and Technology) to measure contemporaneously and in real-time effects on both intracellular growth of Legionella and host cell viability. This methodology has allowed us to rapidly screen 200,000+ compounds for intracellular growth inhibition, while at the same time weeding out compounds that are toxic to eukaryotic cells. In this way, our screening hits are enriched for those with therapeutic antimicrobial potential.

|

(3) Combating multi-drug resistance

Log-fold reduction in intracellular growth of Legionella in high throughput screening assay

Log-fold reduction in intracellular growth of Legionella in high throughput screening assay

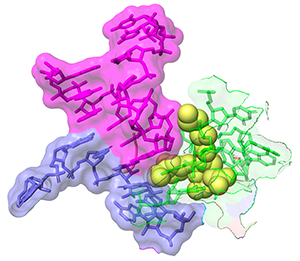

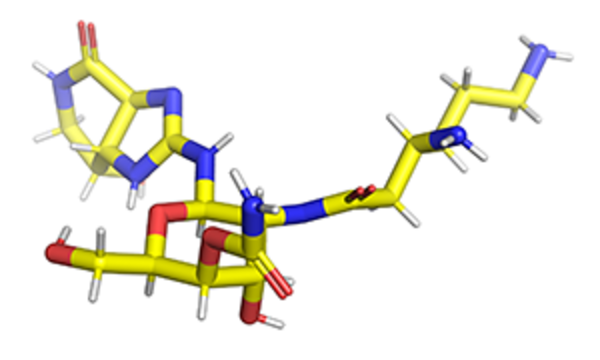

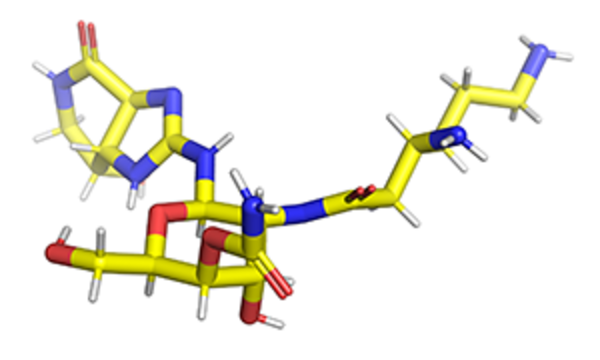

Apramycin bound to 16S rRNA helix 44 from PDB 7PJS

Apramycin bound to 16S rRNA helix 44 from PDB 7PJS

Separately, we participate in a multi-institutional collaboration spearheaded by the Broad Institute to sequence the genomes of CRE and are collaborating with Ashlee Earl's group at the Broad Institute to define mechanisms of resistance.

(4) Developing natural products as next generation Gram-negative antimicrobials

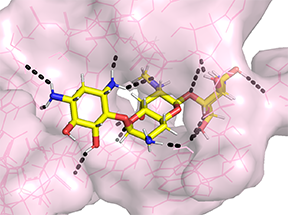

For example, in 1492, Waksman and colleagues, identified a compound class known as streptothricins. Initially, streptothricins generated intense interest, as they were the first antibiotic class identified with potent activity against Gram-negative pathogens. However, limited testing in humans was associated with reversible kidney toxicity. Streptomycin was soon thereafter discovered, relegating streptothricins pretty much to the history books. We took another look at streptothricins and found outstanding activity against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales and Acinetobacter baumannii, including pan-drug resistant strains. In particular, a component of the streptothricin natural product discovered by Waksman, what we now know is a mixture of many structurally related streptothricin molecules, was found to have compelling biological activity both in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, we found that its target is unique and different from other known protein translation inhibitors binding to helix 34 of the 16S rRNA of the small ribosomal subunit. More details are described in our study of Plos Biology. Its binding immediately next to the site of the A-site tRNA provides a plausible explanation for the potent miscoding and resulting rapid bactericidal activity of this natural product.

We are collaborating with the labs of Roman Manetsch and Ed Yu to investigate the structural space around this natural product scaffold and the structural biology of its interactions with the ribosome. Roman's laboratory has developed a total de novo synthesis for streptothricin which supports the exploration of structural activity relationships of the streptothricin scaffold with the goal of finding compounds with enhanced activity that avoids existing resistance associated with acetylation of the beta-amine on the beta-lysine moiety in the molecule by nourseothricin acetyl transferase enzymes found in some strains.

(5) High throughput synergy testing

|

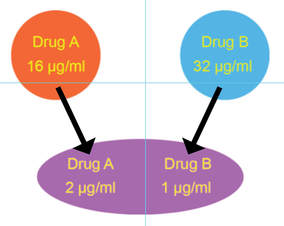

What is synergy? Synergy is the ability of two or more antimicrobials when you used together to have much greater effect than the sum of their separate effects. Or in other words: A + B (observed) >> A+B (expected).

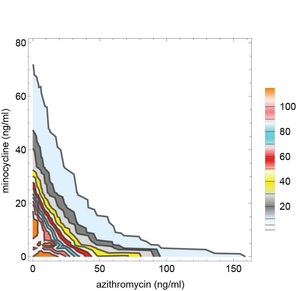

Sometimes synergy is graphically represented by plotting the permutations of antibiotic concentrations that results in inhibition of bacterial growth. These plots are known as isobolograms. Using such analysis, we found that pairwise combinations of azithromycin, minocycline, and rifampin showed strong synergy. See example on the left showing pairwise synergy between minocycline and azithroymycin. In isobologram plots, a straight line connecting the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of each drug indicates indifference, while a concave isobologram curve, such as the one shown, indicates synergy. In this plot, the right most contour line connects points of 99% inhibition relative to intracellular growth of untreated control cultures. Additional contour lines connecting antibiotic concentrations the lead to partial levels of intracellular growth inhibition are also shown. (Isobologram plots to the left and below were drawn with Mathematica. See our recent publication for additional details.) |

|

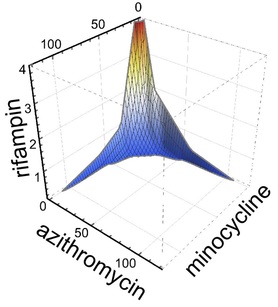

Intriguingly, when used in triple combination, azithromycin, minocyline, and rifampin showed even more potent three dimensional synergy. Specifically, when used in triple combination, only one tenth the concentration of each antimicrobial was required to inhibit intracellular growth compared to when each antimicrobial was tested separately. See graph to the right showing an isobologram surface, connecting points of 99% intracellular growth inhibition, demonstrating a high degree of surface concavity. It is intriguing to consider therapeutic implications and application of this data, especially in disease processes such as lung consolidation where penetrance of antimicrobials may be less than ideal. Just as importantly we found that combinations that might be used in severe community acquired pneumonia such as ceftriaxone plus azithromycin or ceftriaxone plus levofloxacin were not antagonistic. Furthermore, levofloxacin did not show synergy with azithromycin (or any other antimicrobial tested), indicating that the occasionally combined use of azithromycin plus levofloxacin for severe Legionella pneumonia is unlikely to provide benefit.

|

In doing so, we identified multiple antibiotic combinations with activity against the Nevada strain. These included the combination of a number of drugs with colistin. The combination of ceftazidime-avibactam with aztreonam was found also to be highly synergistic, highlighting the potential use of this combination against even the most resistant NDM-1 strains. Demonstrating the power of synergy, none of the same drugs was active when tested alone. In addition, we found that apramycin and spectinomycin were highly active by themselves with compellingly low minimal inhibitory concentration values. The data suggested that these agents could be repurposed to treat highly drug-resistant infections and provide additional motivation for modification of the underlying molecular scaffolds to enhance activity further. You can read the full text of the final accepted article at the following link: "Synergistic Combinations and Repurposed Antibiotics Active against the Pandrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Nevada Strain"

(6) Evicting multidrug resistance plasmids to restore antibiotic susceptibility

We considered it should be possible to block functions critical for plasmid maintenance, thereby expelling plasmids and restoring antibiotic susceptibility. To establish if this were true, we conducted a high throughput screen using approximately 50,000 known bioactives and biologically uncharacterized compounds. In doing so, we identified a number of potent hits with specific mechanism of action and ability to restore susceptibility antibiotic. Several compounds completely stopped plasmid replication and some eliminated all plasmid within the limit of detection of all of our assays (qPCR and even more sensitive bacterial plating assau selecting for a resistance marker on the plasmid). Compounds restored susceptibility to meropenen in a CRE strain driving meropenem MICs will into susceptible range!

One prediction that we had is that potent anti-plasmid agents would indirectly lead to death of the host cell. Specifically as nearly all large, low copy resistance plasmids encode one or several plasmid addiction systems, plasmid eviction should not only restore susceptibility but efficient plasmid loss should also result in death of host bacteria cells. In other words, the bacterial cells will be killed by the stable plasmid addiction toxins that remain after plasmid curing and rapid loss of the cotranscribed unstable plasmid addiction antitoxins. Such was the case. Our findings for the first part of this work are described in PNAS manuscript: "Discovery of small-molecule inhibitors of multidrug-resistance plasmid maintenance using a high-throughput screening approach"

Here we specifically examine the effects on the IncFIA replicon (that's an incompatibility group) commonly found in CTX-M plasmids in E. coli ST-131, a epidemiologically rapidly spreading invasive group of E. coli. We are very excited to be collaborating with the Manetsch Laboratory to develop analogues of potent hits using medicinal chemistry approaches and definition of mechanism of action. We are very interested in what our findings will tell us about resistance plasmid maintenance and biology.

(7) Efflux Pumps

Psoralens were found to be multidrug efflux substrates more generally, and were noted to follow eNTry rulesfor their respective gram-negative penetrance.

(8) Nontuberculous Mycobacterial (NTM) Therapeutics and PK-PD Modeling

Antimicrobials are given in combinations of three or more drugs for treatment. However, they are chosen based on susceptibility of a bacterial isolate to each drug tested individually without consideration of how the multiple agents may interact to augment or diminish their individual effects.

Using advanced technology, the Kirby laboratory is testing the effects of 2, 3, or more drugs together to identify combinations that will lead to improved outcome for patients. Currently, most antibiotic activity laboratory analysis is done by adding each antibiotic at a fixed concentration to organisms suspended in liquid medium and testing effects on organism growth or viability. However, in humans, drug levels rise quickly after an antibiotic is dosed and then fall progressively over several hours with a speed defined by a parameter called a half life. Therefore, when treating an infection, antibiotic exposure is pulsatile. The rise and fall of antibiotics are known as its pharmacokinetics or PK. Our current lab methods therefore are static and do not address pulsatile PK, and therefore are less predictive of how well a drug will work as a human therapy.

To address this limitation, we have set up a system called the Hollow Fiber Infection Model or HFIM. Here organisms are trapped on one side of what is essentially a hemodialysis casettte. Inside, a membrane with a huge surface area allows antibiotics and nutrients to diffuse easily into the bacterial compartment, while the bacterial are held captive for us to evaluate their viability. On the other side of the membrane, we flow medium in which we exactly match the PK for each drug that is already well established in humans. Therefore, pathogens are exposed to antibiotics as they would be in a human infection during treatment. This model is highly predictive of human treatment efficacy. Through use of automated syringe pumps we can model the effects of 3 or 4 drugs given dosed as they would be in humans. Using these and other systems, our goal is to develop life saving therapy for patients, and to develop safer, simpler, and more effective combination treatments for the devastating infections caused by M. abscessus and other NTM.

Some recent publications by our group in the NTM field:

Huang Y, Truelson KA, Stewart IA, O'Doherty GA, Kirby JE. Enhanced Activity of Apramycin and Apramycin-Based Combinations Against Mycobacteroides abscessus. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2025 Apr 9:2025.04.09.648020. doi: 10.1101/2025.04.09.648020. PMID: 40391321; PMCID: PMC12087987.

Huang Y, Chiaraviglio L, Bode-Sojobi I, Kirby JE. Triple antimicrobial combinations with potent synergistic activity against M. abscessus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2025 Apr 2;69(4):e0182824. doi: 10.1128/aac.01828-24. Epub 2025 Mar 14. PMID: 40084880; PMCID: PMC11963555.

Diagnostics

1) The Antimicrobial Testing Gap - Application of Ink Jet Printing, Digital Dispensing Technology.

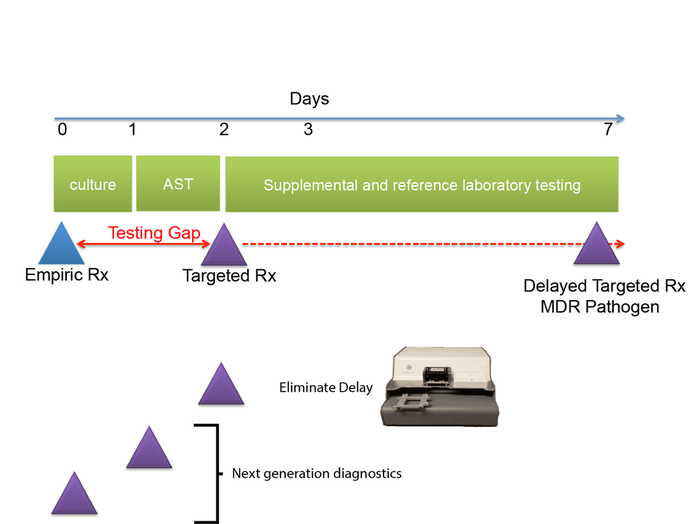

We call the time between when empiric antimicrobial therapy (Rx) is begun, and antimicrobial susceptibility (AST) results are available the "antimicrobial testing gap." Typically this gap may be 2-3 days depending on the time necessary to culture the organisms. Antimicrobial susceptibility results are not practically available until the day after bacterial colonies are isolated. With the dramatic emergence of antimicrobial resistance, especially among Gram-negative pathogens, sometimes we perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) on bacterial isolates, and find that the organisms are resistant to all antimicrobials tested or practically resistant to all antimicrobials if the patient is allergic to or cannot tolerate antibiotics that remain active. We then need to test agents that are more rarely used, for example, colistin, considered one of the agents of last resort for treatment of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Unfortunately, colistin and a number of other agents that may be useful for treatment of multidrug-resistant infections cannot be tested in hospital-based clinical microbiology laboratories. Therefore, isolates must be sent to a reference laboratory where a reference method called broth microdilution or agar dilution testing is performed. This process delays the availability of AST results for several additional days -- time that patients with multidrug-resistant infections can ill afford.

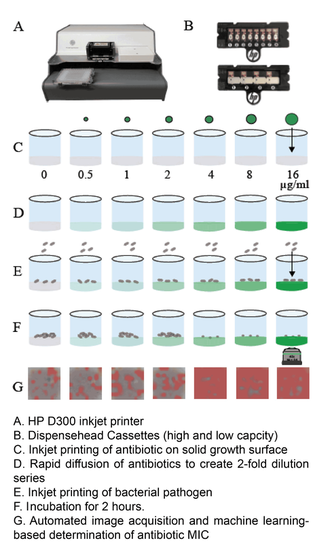

One of the central goals of the Kirby laboratory is to address and shorten the antimicrobial testing gap through use of novel technologies. We recently described and validated use of digital dispensing technology, specifically employing a modified inkjet printer, the HP D300, to enable laboratories to perform broth dilution testing of any antimicrobial at will in 384-well microplate miniaturized format. Importantly, we found that this method was just as accurate and more precise than the gold standard reference method. Importantly, the technology will enable laboratories to facilely perform reference broth microdilution testing in house and therefore avoid the need and long delay associated with reference laboratory testing for drugs such as colistin. A manuscript describing some of our studies with digital dispensing technology was published in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology and further discussed in a press release. Potential applications of digital dispensing technology for addressing several issues in antimicrobial susceptibility testing are discussed in our editorial titled "How inkjet printing technology can defeat multidrug-resistant pathogens" published in Future Microbiology. Our use of inkjet technology for antimicrobial resistance testing and synergy studies (see further below) was highlighted in the CBS sitcom, "The Good Doctor."

Use of inkjet printing to reduce the antimicrobial testing gap.

Synergy: two antibiotics applied together are more activity than when applied separately

2) Synergy

We further used inkjet technology to enable facile performance of synergy testing. The idea behind synergy is that two drugs working together can be more effective than the sum of their individual contributions. Although the minimal inhibitory concentration (see below) of each drug tested individually may be quite high and indicate antimicrobial resistance, sometimes two antimicrobials can act cooperatively driving the MIC for each drug when used together into the susceptible range. Thea Brennan-Krohn from the laboratory recently described synergy testing against a large number of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE). Alarmingly, there are often no therapeutic options left for these multidrug-resistant pathogens. Importantly, we found that for about 90% of CRE there was at least one clinically relevant synergistic combination. However, effective synergistic combinations varied from strain to strain, providing rationale for prospective synergy testing to identify active combinations. Notably, the traditional method for synergy testing requires an inordinate amount of time and labor to perform (45 minutes to set up one combination alone). The inkjet printing synergy method as described in our recent publications in the Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy and follow up manuscript exploring synergy against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive antibiotics with colistin in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy requires only seconds to set up. This technique for the first time provides a practical solution for high throughput prospective or retrospective examination of synergy for a large number of pathogens and antibiotic combinations. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now offers synergy testing for ceftazidime/avibactam + aztreonam using the inkjet methodology originally described in and based on our manuscripts. This testing is available in the CDC Antimicrobial Resistance Lab Network (ARLN) and provides new options for treating otherwise pandrug-resistant pathogens. See the presentation by the CDC (Jean Patel) at FDA Workshop, ("Effort and Resources Addressing Antmicrobial Resistance", slides 10-12). In slide 9, reference is made to the pandrug-resistant Nevada strain, which we show using inkjet printing (quite expeditiously) was susceptible to several antimicrobial combinations and repurposed antimicrobials as published in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

3) Superfast MIcroscopy-Based Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (MAST)

|

We developed a superfast technology for determining susceptibility of pathogens to antimicrobials in hours rather than after a traditional 16-20 hour incubation period, essentially reducing the antimicrobial testing gap by an entire day. MAST combines inkjet printing of antimicrobials and bacteria, advanced microscopy, and machine learning, specifically convolutional neural networks, to determine MIC values within two hours. Importantly, MAST uses off-the-shelf supplies and is highly accurate. The MAST concept was select as a 2017 SLAS (Society of Laboratory Automation and Screening) Innovation Finalist and chosen for a competitive Harvard Catalyst Advanced Imaging and Nanotechnology Pilot Award. A description of initial development of the Microscopy-based Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing platform was recently accepted for publication in SLAS Technology.

|

4) Improvements in clinical microbiology technology

In clinical laboratories, we isolate bacterial pathogens, grow them in pure culture, and test for the ability of antimicrobials to inhibit growth of organisms. Testing is done using doubling dilutions of antibiotics (e.g., 16, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0.5 mcg/ml). The lowest concentration of antibiotic that visually inhibits bacterial growth is called the "minimal inhibitory concentration" or the MIC. The MIC is used as a surrogate for clinical efficacy. Categorical interpretive breakpoints are applied to the MIC values based on the concentration the drug achieves in tissues and body fluids and observations of clinical response. MIC values above a certain breakpoint are considered "resistant"; below a certain breakpoint are considered sensitive, and in between these breakpoints considered "intermediate". Of course clinically, in many situations, we would like to not only inhibit growth of the organism, but to completely eradicate the organism. Forget inhibition -- we want cell death or bactericidal activity! This is an especially pressing concern in situations when the patient's immune system is compromised or pathogens infect a privileged site where the immune response is typically ineffective (e.g., endocarditis, bone infection). There is increasing evidence of "tolerance" or splay between the concentration it takes to inhibit growth of an organism (MIC) and the concentration needed to kill the organism (MBC). Therefore knowledge of the killing concentration would be really useful

The sticky issue is that minimal bactericidal activity (MBC) testing is so cumbersome to perform that no one ever does it; and because of this difficulty, the clinical correlation data for MBC values is also not reliably available. Traditionally, MBC testing is done through serial dilution, plating, and colony forming unit determination for every growth well where growth of organisms is inhibited. The antimicrobial concentration where growth is inhibited by 99.9% is considered the MBC. The MBC procedure is a LOT of work to do even for a single bug-drug combination, let alone testing against the panel of drugs that we want to examine for each clinical isolate. To address the MBC information gap, we have developed novel technology to rapidly determine both the MIC and MBC, a technology that in principle could be adopted facilely in a clinical microbiology laboratory setting and thereby rapidly provide important data for our clinicians. We are currently exploring the potential of this technology to identify tolerance, especially in multidrug-resistant pathogens, to identify optimal regimens that may remain available.

5) The Inoculum Effect: Minor Differences in Inoculum Have Dramatic Effect on Minimal Inhibitory Concentration Determination

The "inoculum effect" is the general observation that the minimal inhibitor concentration (in other words level of resistance) of an organism to an antibiotic increases when a higher density of organisms is tested. This effect is especially prominent for beta-lactam antiibiotics. It is of potential clinical concern in patients during infections where organism burden is high. Some types of infections with high organism burden include abscesses and intra-abdominal infections. Recently, we investigated whether subtle differences in inoculum within the range allowed by current standards can effect the susceptibility testing results that clinical laboratories obtain and provide to clinicians. Our findings for organisms with certain types of multidrug-resistance and antibiotics like carbapenems and 4th generation cephalosporins used to treat such multidrug-resistant organisms indicate that these small allowable differences in inoculum could change the MIC determinations markedly. MICs differences of up to 8-fold were observed when comparing the lowest to high boundaries of the recommended, allowable inoculum range. These MIC differences were large enough to affect whether pathogens were designated susceptible or resistant to the antibiotics tested. These results have profound implications for testing of carbapenemase and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing organisms. Currently guidelines suggest calling these organisms susceptible or resistant solely based upon their MIC. Our data suggest that use of a very accurate inoculum is a prerequisite for obtaining accurate and reproducible MIC results for these types of pathogens. Interestingly, the new drug combination, ceftazidime/avibactam did not appear to demonstrate a significant inoculum effect. Our findings were recently published in the American Society of Microbiology journal, Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

AI Technologist Assist

6) Use of artificial intelligence to advance infectious disease diagnostics

We described the first use of artificial intelligence to interpret microbiology smears. See "Automated Interpretation of Blood Culture Gram Stains using a Deep Convolutional Neural Network" in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology. In particular, we made use of a convolutional neural network (CNN), a deep learninginfrastructure, to automatically interpret blood culture Gram stains and differentiate several organism morphologies. We envision an application called "Technologist Assist" in which image crops analyzed by a trained CNN are presented to a technologist with probabilities of specific diagnoses.. The technologist will then review the images and decide which, if any, in the differential diagnosis should be communicated to clinicians. We view this as a way to synergize the expertise of technologist and AI and enable more nuanced and more reliable diagnosis. See interview with Scientific Inquirer. In our original study, we used 100,000 image crops to train the penultimate layer of the Inception v3 CNN, so called transfer learning, for Gram stain discrimination on a simple office computer. We are grateful to NVIDIA for a providing a high powered GPU through a competitive grant program. This enabled us to apply data augmentation to significantly increase our per crop accuracy over what we had originally reported to greater than 99%. We are very excited about the potential utility of Technologist Assist in future clinical practice. We describe its integration within decision support architectures in Clinics in Laboratory Medicine in a chapter titled Rapid Susceptibility Testing Methods.

7) Interface with Clinical, Academic, and Industry Partners

We maintain close integration with the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, which is also directed by Dr. Kirby, enabling rapid bidirectional translation between basic discovery, assay development, and clinical implementation. A central goal of the laboratory is to apply mechanistic and translational insights to improve diagnostic approaches, antimicrobial strategies, and laboratory practice.

In addition to clinical integration, the Kirby Laboratory engages in active collaborations with academic and industry partners spanning medicinal chemistry, structural biology, and translational infectious disease research. Ongoing and prior collaborative efforts include work with Roman Manetsch and George O’Doherty (Northeastern University; medicinal chemistry), Ed Yu (Case Western Reserve University; structural biology), and Christopher Morgan (Thiel College), among others. These partnerships enable multidisciplinary approaches to antimicrobial discovery, resistance mechanisms, and diagnostic innovation.

Research projects may involve clinical microbiology fellows and pathology residents, who rotate through the research laboratory as part of their training, further strengthening the interface between discovery research and real-world clinical microbiology practice.

The laboratory has experience supporting collaborative evaluation studies relevant to translational decision-making and pre-clinical development.

Additional Team Current Members are in the process of being added. We have a wonderful group of additional undergraduates (Northeastern University, Boston University, Brandeis), post-college graduates, and high school students contributing to our efforts. OpenScholar does not yet have functionality to designate and list Former Lab Members. Please see https://www.kirbylab.org/personnel.htm for full listing

For Kirby Lab News, please see https://www.kirbylab.org/blog

See positions page. We are seeking postdoctoral fellows, graduate students, undergraduates, medical students, all those interested in addressing antimicrobial resistance through antimicrobial discovery, advanced diagnostics, and translational research